On the morning of February 12, 2019 England’s greatest goalkeeper died. Gordon Banks was the winning keeper in Englands 1966 World Cup victory and had “The Greatest Ever Save” four years later against Pelé. He was the hero of many children, even an Irish lad from the north.

I met Don Mullan, a humanitarian and human rights activist, in Dublin several years ago and we struck up a friendship that remains. This year I invited him to speak to our students in the Lewis Honors College and he arrived on the evening fo February 11th. When he emerged into the baggage claim area he looked tired, as you might expect from a trans-Atlantic flight, but he was weary. His hero was dying. I will let Don tell the story in his own words, but over the years Don had become friends of the great Gordon Banks and his family. As we embraced he said, “I have been praying to Mack for our dear friend Banksy, that he would welcome him into heaven.”

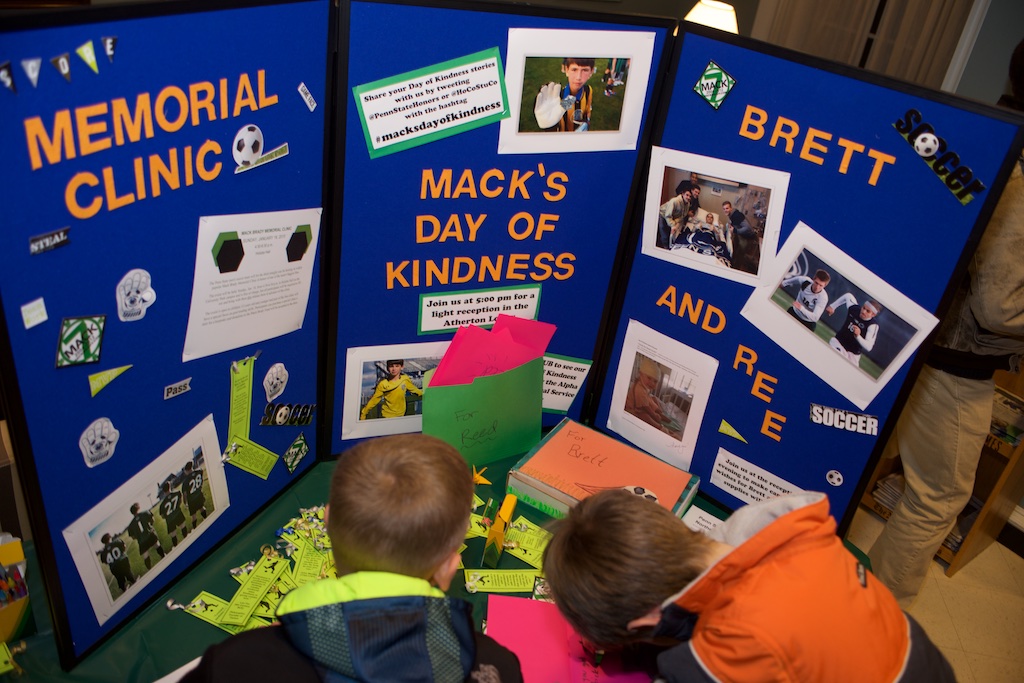

Don was invited by the Banks family to address the world, representing all fans everywhere. He took with him the Mack cap I gave him and sent back this picture. Please read his eulogy below. It is powerful, moving, and about so much more than sports.

GORDON BANKS: A Hero Who Could Fly

Eulogy by Don Mullan

Stoke Minister Church, Stoke-on-Trent, England

4 March 2019Distinguished guests, dignitaries and friends, I must begin by thanking Mrs. Ursula Banks, and her children, Robert, Wendy and Julia, and extended family, for affording me this singular privilege of saying goodbye to the people’s Knight – the supreme gentleman of football – our beloved ‘Sir’ Gordon Banks. I extend to you all my heartfelt condolences.

I am conscious that I am but one of many thousands of Gordon Banks fans, especially goalkeeping fans, across the globe who mourn his passing. These include Graham Plimmer, England; Eric Talavet, France; Anthony LaPaglia, Australia; and Thor Helge Bergan, Norway.

Last year an old Super 8 movie of a children’s football game was found in the Creggan Estate, Derry, in the north of Ireland. There is a wonderful innocence in the 1967 footage of boys emulating their footballing heroes, with goalposts of bundled coats and jumpers. To us, these were the goalposts of unbranded stadia like the old Victoria Grounds, Anfield, Old Trafford, the Brandywell and Wembley.

The footage includes an 11-year-old goalkeeper, in a yellow top, for I was the England number one goalkeeper, Gordon Banks – world cup winner, and soon to be six times FIFA Goalkeeper of the Year.

There is nothing in the movie to suggest that a few years later gun battles between the British Army and IRA would rage along the field where the game is played; that civilians and soldiers would die; and that an unbridgeable chasm would open between my community and the Army, especially after the introduction of Internment in the summer of 1971 and Bloody Sunday in 1972.

Bitterness reigned in the aftermath of the tragedy and as I turned 16, the temptation to embrace the path of violence increased.

However, two years earlier I had a life changing experience, thanks to my beloved working-class father, Charles. Just six-weeks after ‘That Save’ from Pelé, my boyhood hero travelled to neighbouring Co. Donegal with Stoke City FC for a preseason friendly. Seeing my hero from the terraces was my only expectation.

But, unknown to me my father hid my famous scrapbook – a 500-page Crown wallpaper book – in the boot of his old Vauxhall Victor. We pulled into Jackson’s Hotel and he told me to wait with my mother and a friend.

A few minutes later he emerged, animated and calling, ‘Don, come here! Come here!’ Confused, I followed him into the hotel foyer and immediately spotted my scrapbook with a tall man leafing through it. Then my father spoke the magic words: “Here he is Mr. Banks.” And with that, Gordon Banks turned around. Words cannot adequately describe that moment. It was, quite honestly, like being granted an audience with God!

I was given unforgettable goalkeeping tips from the maestro. And to my parents delight he encouraged me to work hard at school before autographing my scrapbook: ‘Best wishes Don, Gordon Banks’. But my abiding memory is of the gentle courtesy and respect he showed to my mother and father, no doubt seeing in them a reflection of his own.

The Irish ‘Troubles’ intensified and a few years later I was asleep in my bedroom when I was awakened around 4 am with the roar of armored vehicles outside our house, followed by fists pounding on our front door. An English voice shouted, ‘You’ve 10 seconds to open the door or we’ll break it down.’

I rushed from my bedroom, calling to my parents that it was an Army raid. I was swept aside as 15 or more soldiers stormed in. I followed one soldier into my bedroom. He seemed to freeze as he surveyed the wall. Instead of Republican and IRA paraphernalia the wall was decorated with posters of the 1966 England World Cup winning team, of the 1972 Stoke City League Cup winning team, and giant posters of Gordon Banks. Visibly confused he asked, ‘What’s this mate?’ I told him that Gordon Banks was my hero and pulled from under the bed my scrapbook and showed him my prized Gordon Banks autograph.

“Sir!” he shouted, “come and see this.” Perhaps thinking a weapon cache had been discovered the officer arrived and soon a line of British soldiers were queuing to see my Gordon Banks autograph. The aggression suddenly dissipated and soon I was sitting on our stairway holding court with the British Army discussing Anglo-Irish affairs. When word came through the radio that I was to be arrested the officer assured my mother that I would not be harmed. An hour later, as I stood facing a wall in an Army base, the officer told me I was free to leave – and even offered me a lift home!

Gathered as we are on the ancient hallowed grounds of Stoke Minster where the great Josiah Wedgwood is buried, I must express my gratitude to one of his descendants, BBC Radio Stoke’s Tim Wedgewood, for rekindling that moment of magic my father ignited in 1970. In 2004, following an interview about one of my books, Tim asked me about my lifelong admiration for Gordon Banks. Unknown to me he had Gordon Banks listening and 34 years after my first audience with ‘God’, I was now talking to him live on radio. I told him that my bucket list included having a photograph taken with him. “Anytime, Don,” he told me, and invited me to Stoke.

Thanks to Terry Conroy, I traveled over in 2005 with my 14-year-old son, Carl, and Terry’s two nephews, Paul and Mark. This was an emotional reunion, even as a 49-year-old adult.

Beforehand, the songwriter, Phil Coulter, also from Derry, famous for ‘Puppet on a String’ and the 1970 World Cup song ‘Back Home’, advised me to be careful. ‘It can be a dangerous thing to meet your boyhood hero as an adult’. Phil was afraid that I might be disappointed.

Was I? Absolutely not. In fact, my admiration and love for Gordon Banks increased. I realised the courteous, gracious, kind and gentle man who had shown so much respect to my parents in 1970 was the same man I was standing before. He was not only the world’s greatest goalkeeper, I had a colossus of humanity for a mentor.

In the past few weeks, I’ve been deeply touched at how the people of Stoke and Staffordshire, and fans from home and abroad, have festooned with reverence and respect, Andrew Edward’s magnificent statue, erected with the support of the Gordon Banks Monument Committee.

In the often-vexed history between Ireland and England, perhaps this is the first monument ever championed by an Irishman to an Englishman. I hope so. For me, it was an outpouring of gratitude to an English sporting hero who, in the best way imaginable, changed the trajectory of an Irish boys’ life.

During her historic visit to Ireland in 2011, Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II spoke words that touched many. At a banquet in Dublin Castle she said:

“…it is impossible to ignore the weight of history… the relationship [between Ireland and Britain] has not always been straightforward; nor has the record over the centuries been entirely benign. It is a sad and regrettable reality that through history our islands have experienced more than their fair share of heartache, turbulence and loss. These events have touched us all, many of us personally, and are a painful legacy…”

Five years before Her Majesty spoke those words, I had written a memoir called ‘Gordon Banks: A Hero Who Could Fly’. It is my eulogy to an English icon who allowed me to become his friend, and the friend of his family. Recalling my boyhood teammate and best friend, Shaunie McLaughlin, tragically killed in a car crash in 1976, I wrote the following words. Words that encapsulate all that Gordon Banks has been to me:

“[Shaunie and I] lived through exceptional moments together: we faced what were for us epic choices about life and death and war and peace.

At the same time, we lived in an era when sporting heroes were ordinary and unassuming men whose very modesty was the oxygen of dreams. And across the water, on a neighbouring island with whom we Irish had been in conflict for centuries, I had a hero who could fly. His name is Gordon Banks.

From being a timid, fearful young boy, he taught me that impossible doesn’t exist. Unknown to him he helped save a young fan from making choices that had brought too much sorrow and sadness to Irish and British alike.

‘Who knows? Perhaps it was his best save ever.”

Farewell, kind friend. Thank you, Gordon Banks!

Don Mullan

European Ambassador, Pelé Little Prince Children’s Hospital Research Centre, Brazil

Consultant, United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)